Nuremberg was still bombed out and there weren’t many quarters for dependents, but after a while Joe was able to find an apartment for them and Marie sailed over to join him. Joe was in ordinance still, but also working with the refugee program.

“I landed in Rotterdam and had to take a train to Nuremberg. I knew just a bit of German, but not nearly as much as Joe did. Sometimes I don’t know how I did it. At first we lived with this German Frau and finally were able to get quarters out in a little town called Eibach. We were housed in one of two buildings that had been German SS quarters. I loved it there. I had a garden, but I didn’t really have much to do there and I went to work for the Army in special activities, in motion picture service. They had charge of all the theaters, in North Africa, the embassies, all around,” Marie reminisced.

“We took a leave in 1954 to go to Luxemburg. I had promised my dad I would visit where his father was born. I still had relatives there and one cousin took us all over the country. We went out to this little village to see the home place. That part of the family had all immigrated to the United States. A woman who lived next door had bought the property. My great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents had owned the property. It was an old stone house with the stable and everything under one roof. But in earlier times the farmers would go into the villages at night for protection and come out to the farms in the daytime to work.

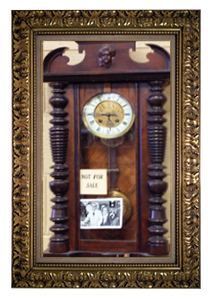

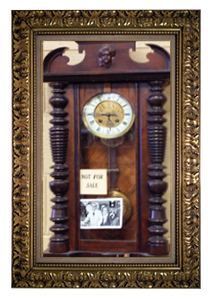

“The woman who owned it when we went there took us through the house and told us that if there was anything there we wanted, to “take it; it’s yours.” She was storing hay and grain in it. She had never lived in it. She pointed out a clock on the wall and said, “That clock was hanging there when I bought the place (50-60) years before). It’s yours. You have to take it,” Marie laughed.

“But we didn’t want it then,” Marie continued. “In those low countries where it’s so damp and cold, and in that old stone building with no heat, you can imagine what kind of condition it was in. The veneer back was in curls and the springs were gobs of rust, but we ended up taking it and Joe put it in the trunk of the car.

“It was a Gustav Becker clock, made in Germany. Becker was a very prolific clock maker and his clocks were everywhere. He made them in Freiburg, Silesia, not the Black Forest Silesia, the Upper Silesia. His company was bombed out in World War I and never rebuilt. His inventory that was left was sold to another firm called Junghans."

Joe and Marie’s first child, a son named Marty, was born in 1955 while they were in Germany. Marie said that the Army needed help so badly that she went back to work a month after Marty’s birth. In the meantime, the clock continued to ride around in the trunk of the car. Finally, one day in Eibach, Joe decided to go golfing. When he started to put his golf clubs in the trunk, it started to rain. But there was the clock. He had forgotten all about it and decided then and there that he would do something with it.